This story is part of the series Health and Healing for Cambodian Survivors.

FRESNO, Calif. — Almost 50 years ago, the Khmer Rouge took control of Cambodia leaving its mark on history as one of the most brutal communist regimes to seize power. Under dictator Pol Pot, millions of Cambodians were killed in a systematic genocide that lasted nearly four years. Thousands fled the country. Today, many of those survivors live in California, a state with some of the largest concentrated populations of Cambodian refugees. One thing many have carried with them is the trauma of the experience. Treating this trauma is complex: Language and cultural barriers make it hard for many to access mental healthcare.

I didn’t personally experience the Khmer Rouge regime, but I was born in its aftermath. Both my father and mother and their families lived through the horrors of the genocide from 1975 to 1979, when many died from forced labor, starvation, murder and torture. It’s estimated at least 2 million people died. Those who survived the genocide are still dealing with the trauma from that time.

I was born in Khao-I-Dang, one of the main refugee camps in Thailand that housed thousands of survivors. In the 1980s, my family was sponsored to come to the U.S., where we first landed in Los Angeles. By the time I was a teenager, we had made our way to Fresno, which is now home to more than 6,700 Cambodians, according to the 2015 U.S. Census.

For me, the genocide existed only as fragmented stories I occasionally heard from my parents and grandparents - always spoken in “Khmer” or Cambodian and usually sparked by conversations around food at the dinner table. These stories often were told to highlight how abundant our lives were now compared to the time of Pol Pot

A 2005 RAND Study surveyed a group of refugees - all adults who lived through the Khmer Rouge. In the group, 99 percent reported experiencing starvation. And 90 percent had a family member or friend murdered.

When Vietnamese forces drove the Khmer Rouge out of power in 1979, survivors like my family fled to refugee camps in Thailand. Hundreds of thousands of Cambodians resettled in the U.S., Canada, France and other countries.

During the 1990s, more than 150,000 Cambodian refugees reached the United States. Today, when their descendants are also counted, more than 316,000 Cambodians are part of U.S. communities, according to the Pew Research Center.

A third of that population is in California, with the largest pockets in Long Beach (40,595), Stockton (12,520), Orange County (9,183) and Fresno (6,718).

Studies have found that, even decades later, Cambodian refugees who lived through the Khmer Rouge still suffer from high rates of psychiatric illnesses. Some 62 percent of the Cambodian refugees in the RAND study were found to suffer from PTSD and 51 percent had depression. Often they had both.

But accessing mental health treatment is difficult for this group of survivors. There is a negative stigma in the culture around seeking mental health care and because there are few service providers who speak “Khmer,” many in the community don’t feel comfortable seeking care at all.

It wasn’t until much later as an adult that I learned about this need for mental healthcare. I started contracting as an interpreter at medical and social service appointments. As I met other Cambodian elders outside of my social circle, every appointment revealed more and more the widespread effects of the genocide’s trauma. Every single person I interpreted for was impacted on some level in the mind, body and spirit.

In place of mental health care, many Cambodians turn to spirituality as a way to deal with the trauma. For Cambodians, the temple is a sacred gathering place to find comfort and community.

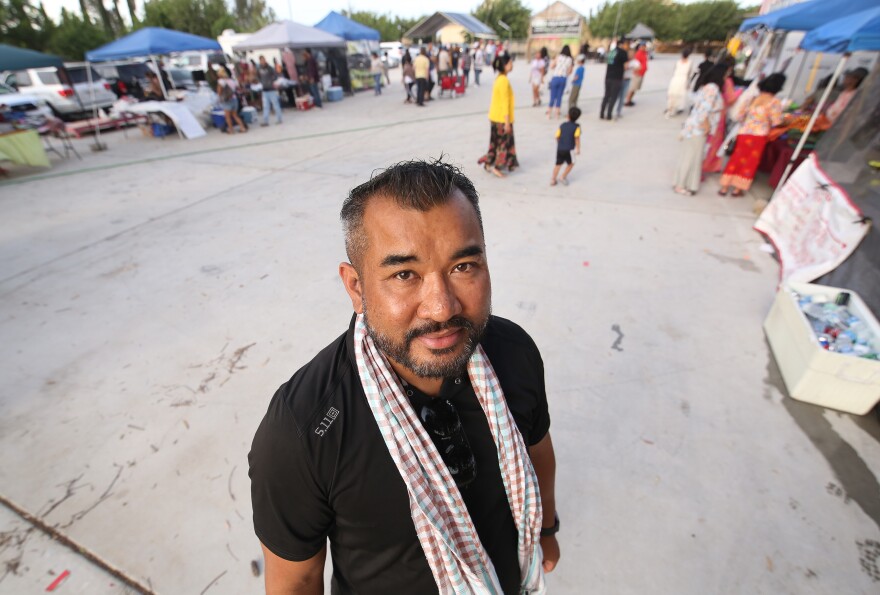

This sense of familiarity is why Danny Kim, a Cambodian refugee who is now a Fresno police sergeant, spearheaded the effort to start the Cambodian Night Market at Fresno’s largest Cambodian Buddhist temple, a one-story building decorated with a colorful trim or red, turquoise and gold carvings, sculpted columns and a majestic golden spire.

“This is the benefit, not just the temple, to showcase the architectural design, [but to] showcase our culture,” Kim said..

The night market is held monthly, every first Friday from July to November. At tonight’s event, the music is on and lines have formed outside a medley of colorful tents set up in the open space of the temple grounds. Some are drawn by the savory scent of grilled meats or are tempted by other Southeast Asian treats.

“Secret sauce right here,” Kim says, pointing to a Cambodian vendor making her family’s papaya salad recipe.

Another woman is selling goods imported from Cambodia - food, fabrics, souvenirs. It’s all a familiar sight to Kim - who was inspired to start the market in southeast Fresno last year after visiting a vibrant night market in Siem Reap, one of Cambodia’s most popular tourist destinations.

“It's about allowing people to have at least something to look up to, look forward to,” Kim said.

During the night market, the temple transforms with live Cambodian music on the stage and dancing. Occasionally, one spots the orange robes of a Buddhist monk in the crowd.

As one of only two Cambodian sergeants with the Fresno Police Department, Danny plays a big role in understanding the community, even when not in uniform.

“They're so proud to be Cambodian. They're so proud to be a part of this,” he says.

The event is a dedication to and a celebration of a culture that was almost lost.

This story was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 California Fellowship.

_______

This is the first part of KVPR’s five-part series, “Health and Healing for Cambodian Survivors.” Continue reading to hear from survivors of the genocide, people helping treat the trauma and from others who are finding healing through community-building.