When Saul Ruiz heard about the McKittrick oil seep, which first occurred in May and is now being cleaned up by Chevron and state agencies, his first reaction was worry: Worry for the McKittrick residents and environment nearby, but also for residents of other similar communities. “My worry was that problems like these could expand to other communities like Taft, Buttonwillow, Lost Hills,” he says in Spanish.

Lost Hills: A community of 2,400 tucked between the I-5 and an oilfield about 20 miles north of McKittrick in Western Kern County. It’s where Ruiz settled 34 years ago and now lives with his wife, eight of his nine kids, and dozens of chickens. “What I like about this town is that it’s very relaxed, very tranquil,” he says. “Aside from the poor air quality, I love this town.”

Air quality is a perennial concern in Lost Hills, where Ruiz worries it’s worse than elsewhere in the Valley. Residents complain of smells like rotten eggs and chemicals. When his daughter was young, she landed repeatedly in the emergency room with asthma attacks. If the air is worse here, he wondered, is it because of the highway running through town, pesticides used in the nearby orchards, or something else? “I think it has a lot to do with being so close to the oilfields,” he says.

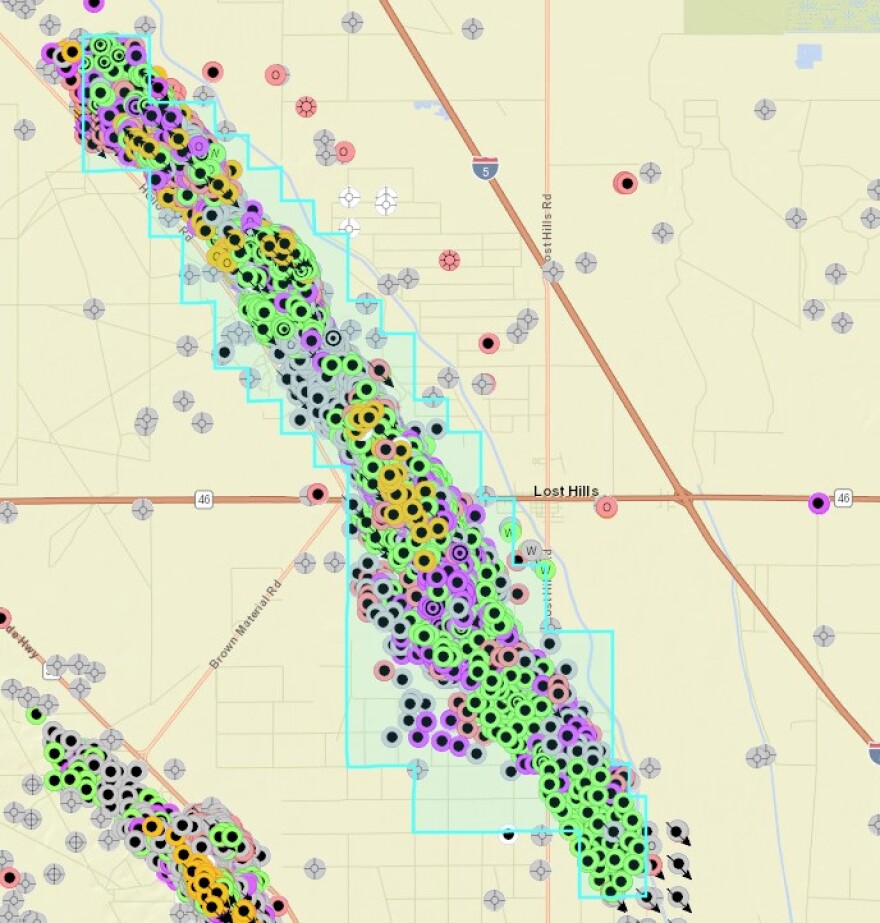

More than 5,000 wells, the nearest only a quarter mile away from Lost Hills, stretch toward the horizon to the northwest and southeast. It’s one of the 10 most productive oil and gas fields in the state.

But it’s hard for Lost Hills residents to know what’s in their air. The nearest government-funded air monitor is 30 miles away in Shafter. So to better understand his environment, Ruiz joined the Lost Hills Committee in Action, a grassroots group trying to improve the quality of life in town. He’s now the president. Last year, after public meetings and discussions, the committee and two non-profit partners won a $400,000 state grant to place seven high-tech air monitors around town.

Finally, Ruiz thinks, he might get some answers. “It brought new life into me,” he says. “I was really excited to know that for the health of my family, that we’d be able to start addressing the contaminants in the air.”

“The goal with these monitors is to monitor the different contaminants that’re commonly found near oil/gas sources and ag sources,” says Jesus Alonso with the environmental advocacy group Clean Water Action, one of the partners on the grant. We meet at a food truck on Lost Hills’ main drag, where families and laborers are eating tacos and burritos. Alonso gets a tamarind-flavored Mexican soda, though he’ll be back for a carne asada burrito later in the day.

Beginning this past May, he explains, the monitors, which look much like white electrical boxes, were placed in various locations around town and will be recording air quality until December 2020. Provided by the environmental consulting group Blue Tomorrow, their data available live online, the monitors are measuring pollutants like particulate matter, ozone, volatile organic compounds and methane. “They'll be armed with the knowledge to not only create change with their personal lives, but create change for their community,” Alonso says.

Augustin Bernardino, who’s lived in Lost Hills for 47 years, says the wind carries many odors into town. There’s the wind from I-5 the east, carrying particulate matter that’s increasingly being linked to respiratory and cardiovascular problems, and the wind from the pistachio and almond fields north and south of town, where many pesticides are known irritants and one commonly applied chemical has been revealed to cause neurological problems. However, “the most toxic one is the wind that comes from the west,” Bernardino says, “and west of us is the oilfields,”

Do residents have reason to be concerned about petroleum emissions? The research says maybe. “The reason why is we really cannot put people in labs and control everything else that’s happening to them,” says Lisa McKenzie, a public health researcher at the University of Colorado who studies petroleum development in urban areas. “People are exposed to a lot of things.”

Without access to laboratory studies with control groups, she’s built her research around observing large populations over long timeframes. In neighborhoods near petroleum development in Colorado, she’s found an increased risk of congenital heart defects and childhood cancers among those raised near oilfields.

What she demonstrated, however, was a correlation, not direct cause and effect, which she warns takes time. “I often refer people to looking at how long it has taken to make those links between smoking cigarettes and cancer and some of the secondhand smoke studies,” she says.

Similarly, a 2015 study by the Washington-based environmental group Earthworks called out Lost Hills as one of two California communities especially at risk from oil and gas impacts to both air and drinking water quality. After collecting air samples and infrared imaging in the Lost Hills oilfield, author Bruce Baizel found traces of methane and isoprene, an organic compound that’s been designated a possible carcinogen.

“The chemicals are there in the air and the people have symptoms that are consistent with the kind of symptoms that, if you do rat research in a lab or something, the rats would have,” Baizel says, referring to symptoms like skin irritation and chronic coughing. Like McKenzie, however, he couldn’t demonstrate cause and effect.

The state also recognizes gaps in air quality knowledge related to petroleum development. Earlier this year, the state Air Resources Board, or ARB, launched its own program to monitor air quality specifically near oil and gas sources. The program’s first study community is Lost Hills, where monitors will be in place for six months until December 2019. “We really don’t know what we don’t know,” says ARB’s Carolyn Lozo. “There is the potential to have impacts from oil and gas, as there is the potential to have impacts from other sources as well. That’s exactly what we’re hoping this study will tell us.”

For its part, the local San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District tracks emissions using 39 monitors distributed across the Valley. “We’re confident that the network we have established captures the peak for the Valley, which is what we really want to know,” says Jon Klassen with the air district. “But of course, if there’s projects out there that can collect data in these areas that we haven’t had historical monitoring, that’s always good to know, to see that data.”

The Western States Petroleum Association turned down an interview request for this story, but in an email statement, President Catherine Reheis-Boyd writes the association supports the ARB monitoring program “throughout the state and especially in the Lost Hills community due to the community’s proximity to both mobile and stationary sources...That program provides important data to the industry and all Californians concerned about air quality.”

In Lost Hills, Saul Ruiz is so enthusiastic about that data, he agreed to place one of the monitors just outside his house. The one he’s most excited about, however, is at the point in the community that’s closest to the oilfields: The elementary school.