This story was updated on 10/30/2025.

When Dayana migrated to the United States from Perú in 2022, her main goal was to finish her education.

Dayana’s family was split apart – her older brother and mother stayed in Perú. Meanwhile she and her father, Roberto, left to seek out better economic opportunities and safer living conditions. They declined to share their last name for publication due to safety concerns.

Perú, like many Latin American countries, faces significant challenges with poverty, inequality and political instability.

“I [didn’t] want that for my daughter,” Roberto said in Spanish. “For me, I want my kids to fly. That’s what parents are supposed to do.”

The two landed in Fresno as undocumented immigrants. Roberto got a job working in industrial maintenance for a meat production company while Dayana enrolled as a junior at McLane High School.

With her newcomer status and lack of English language skills, Dayana worked diligently to catch up with her peers. She was placed in English Language Development (ELD) classes and basic math and science courses. She says she felt an overwhelming sense of support from her classmates and teachers.

“There were teachers who understood me,” she said in Spanish. “I had barely arrived in the country. Everything was completely new to me. From the cafeteria to the classes, everything was totally different from what education was like back in Perú.”

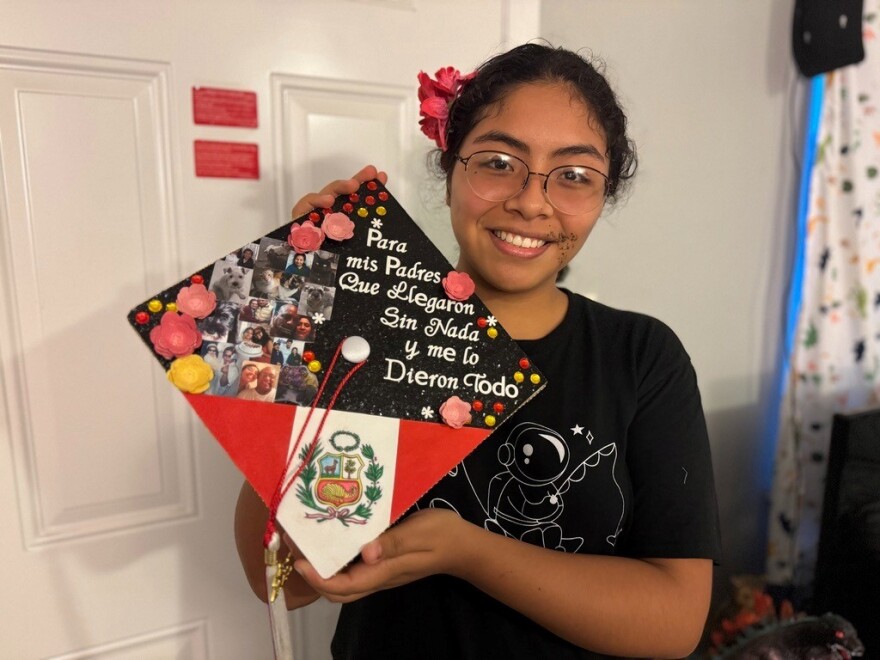

Dayana became highly involved at her schools through clubs and volunteering. She was even named valedictorian when she graduated earlier this year.

Thinking about college during her senior year, Dayana had applied to major universities in California – UC Berkeley, CSU Long Beach, UC Merced, Fresno State and UC Davis. She was accepted by most of them. She started dreaming about moving away from Fresno and living the college life in a new city.

But Dayana quickly realized what that would mean – and what financial and mental health struggles would come along with being on her own, especially as she and her father started the process of seeking legal documentation.

Not long after, federal immigration raids started in Los Angeles and other parts of the state.

Students with immigrant backgrounds, like Dayana, across California and the country are now grappling with how to continue pursuing their academic dreams as immigration issues become more prevalent.

“I had to consider what was happening in the news about ICE, that the president was going to start making these changes that were going to negatively impact immigrants,” she said. “I had to ask myself, ‘why would I move to such a big city if something could happen to me?’”

The stress of leaving family behind

For those students from immigrant families who do decide to leave home, the fear remains constant.

Edison graduate Montse, who declined to share her last name for safety concerns, explained how that decision was difficult to make.

Her family migrated to Fresno from Mexico in the early 2000s. Montse is the only person in her family who has U.S. citizenship – both her parents and an older, disabled sibling are undocumented.

Montse was surprised when she received early admission to UC Berkeley. At first, she was excited to be chosen to attend the highly prestigious school. But her excitement dwindled when she realized what moving to Berkeley would mean – leaving her family behind.

“I started thinking about what would happen to my family if they were stopped by agents,” she said. “My parents don’t speak a lot of English and my sister has a lot of needs.”

Montse asked her friends, teachers and mentors for advice and made her choice.

“I thought to myself, ‘this might be my only chance to go,’” she said. “I decided that the benefits outweighed the risk.”

Montse said that as she started her first semester, she felt at ease going to her classes and making friends and finding community through Latinx clubs. But she also feels close to home because she drives from Berkeley to Fresno every weekend to help her parents around the house and volunteer in her community.

She said a lot of the students she’s met so far share similar fears for their families. Those fears only intensified after the Supreme Court ruled federal agents could stop people in Los Angeles for speaking Spanish or appearing Latino amid immigration crackdowns in the city.

Such concerns partially inspired her to pursue a double major in Law and Ethnic Studies – so she can become an immigration attorney in the future.

Her family’s safety and immigration concerns will always be on her mind, Montse said. But while she’s in school, she won’t let it hold her back.

“I can’t let my fears take over,” Montse said. “I’m going to try my best to stay focused and be the first in my family to graduate college.”

Organizers seeing patterns in young people

In 2024, first-generation, second-generation and undocumented students made up nearly a third of the 19 million students enrolled in higher education institutions in the U.S., according to the Higher Ed Immigration Portal. In California, nearly a fifth of students in higher education fall under that umbrella.

First-generation college students – or students who are the first in their family to attend university – already face significant challenges with financial hardships, mental health concerns, and biases related to their first-generation status. Undocumented students are also ineligible to receive federal financial aid. As a result, many rely on state aid, institutional aid, or private scholarships to afford classes.

The added stress of immigration enforcement for themselves, their family members, and community impacts those students at every grade level. And while California law prohibits immigration enforcement agents from entering public K-12 schools, the same protections aren’t promised on college campuses.

Johnsen Del Rosario of the Youth Leadership Institute works with many high school students in Fresno. He said that students are highly aware of the political landscape they live in. During the first rounds of immigration enforcement in Los Angeles, Del Rosario said it sparked fear and uncertainty.

Del Rosario noted how Los Angeles is only a few hours drive from the Valley and Fresno. “And now these young people are starting to think Fresno could be next.”

Del Rosario noted that some students came to him with worries about their future. He observed students who decided to skip their classes, stopped attending YLI workshops and events. Some even talked about changing or deferring their college plans because of immigration concerns.

“There are things that we know that our young people want to do, but because of the implications of what could happen, they stop themselves.” Del Rosario said. “It’s very sad for a young person not to pursue [their] passions because of how dangerous it is right now.”

The most important way to uplift these students, according to Del Rosario, is to continue spreading awareness and resources about immigrant rights.

“We need to make sure that our young people in our communities know what to do in case it does happen,” Del Rosario said. “We’ve been passing out red cards at every community event just to make sure that folks have what they need in order to make it another day.”

‘The benefits outweighed the risk’

Dayana ultimately decided to stay in Fresno and attend community college. While her dreams of moving to a new city are on hold for now, she doesn’t regret her decision.

“I’m a little sad for not having the typical college experience that most students have at my age,” she said. “But I’m hopeful I’ll be able to have those opportunities in the future if things get better.”

In the meantime, Dayana’s taking general education courses and is planning to apply to a nursing program. She is open to transferring to a four-year university in the future, and is happy to consider all her options when the time comes.

“I’ve learned so much already from excellent teachers. I’m taking advantage of a lot of the things they’re offering me,” she said. “Knowing that my home is close by, it’s a peace of mind.”