This story received a 2022 Golden Mike Award from the Radio Television News Association of Southern California. Read about other winners here.

Earlier this year, Jeff Gambord realized he couldn’t remember the last time he had a physical exam. So he requested his medical record from Coalinga State Hospital, the psychiatric facility where he’s been a patient since 2006.

Gambord learned it’d been more than a year, and he was curious if this was common—so he encouraged others to request their records, too. “When we went back and looked up a couple other patients on this unit, some go back as far as two or three years as not having received exams,” he said.

This at a facility that’s required to provide physicals at least once a year, and more often for serious ongoing conditions. “I was quite shocked to find this out,” Gambord said.

Gambord is 61. The average age at Coalinga is 55, older than any other state hospital or prison, according to state data. That’s because most are committed here for life. They’ve already served prison sentences for their crimes, years or decades behind bars, but a court later deemed them a danger to society and sent them to Coalinga.

These men are here for psychiatric rehabilitation. Three-quarters of them, including all the patients interviewed and described in this story, are convicted sex offenders. But their age means many are developing chronic conditions like heart disease, diabetes, and obesity. Gambord and others worry they’re not getting the preventive care they’re due. “The significance of the exams not being done according to policy is that underlying medical conditions in terms of cancers and other pathologies are not discovered until they become symptomatic,” he said.

The California Department of Public Health (CDPH) shares their concerns, at least on a small scale. In May, in response to a complaint from Gambord, the agency cited the hospitalfor not providing timely physicals and maintaining accurate medical records for at least one patient. “This failure resulted in an incomplete medical record for Patient 1 and potential risk for medical needs not being met,” the CDPH’s statement of deficiencies read.

The Department of State Hospitals (DSH), which oversees Coalinga, turned down an interview request from KVPR, but did respond to questions by email and also shared the state’s citation. In response to the state, the agency agreed to audit patient medical records for missing physicals, and to step up exam-related bookkeeping and training.

However, the men’s concerns don’t stop there—their list of complaints also includes not being sent to specialists when necessary, not being given the medications and medical devices they need, andan inadequate COVID-19 response.Some with uncertain immigration status were so concerned about the pandemic thatthey said they’d rather be deported than remain at the facility.

The patients’ concerns are understandable. Last year, 30 Coalinga patients died, a sum of more than two percent of the patient population. An FM89 investigation of state data revealed that the death rate was almost twice the average among California’s entire state hospital system, and almost seven times higher than the rate within the state prison system.

Congregate living facilities like these were hit hard by COVID-19. But even after accounting for the pandemic, Coalinga reported an inordinate amount of deaths in 2020. Its aging population is one reason, but patients still believe many of those deaths could have been prevented, and documents from state oversight agencies raise questions about the hospital’s medical care. All this despite exorbitant amounts of public taxpayer money being spent on these men.

“My experience with Coalinga State Hospital is...they were not concerned about care of the clients, and that the care was deficient,” said retired attorney Terry Shenkman, who represented around a dozen Coalinga patients near the end of her three decades working for the Los Angeles County public defender’s office. “When COVID broke out, I was concerned about what would happen to the patients at Coalinga State Hospital because they had complaints about the condition at the hospital before they were dealing with COVID,” she said.

They included complaints about some illnesses being overmedicated and others not managed at all. She says one client, who barely spoke English, was mistreated because the hospital failed to provide him with an interpreter.

“I do believe there’s an attitude of, these people’s lives aren’t as valued as other people’s lives,” Shenkman said. “There’s not an attitude there of, ‘ok, you’re here, we’re going to try to help you.’”

Among the 30 men who died in 2020, a death certificate analysis revealed the most common causes of death were heart disease, respiratory conditions, liver and kidney problems, and diabetes. Eleven died of complications related to COVID-19, a case fatality rate that’s still higher than at most other state facilities. Most state prisons, which house two to three times more patients than Coalinga, reported fewer COVID-related deaths than the hospital, even if their case totals were higher.

According to DSH, each Coalinga patient costs taxpayers nearly $300,000 every year, three times the cost of each prison inmate. Much of that goes toward round-the-clock psychiatric care, but patient James Hydrick wants to know how much is spent on medical care. “We don’t know, that’s what we’re asking them,” he said.

Just as patients have asked for their medical records, they’ve also been submitting public records requests for itemized medical bills and other hospital expenses.

In the past, the state auditor has uncovered wasteful spending at the hospital: In 2007, for instance, the agency reportedtens of thousands of dollars spent on security vehicles instead being used for employees’ commutes, and in 2012,an employee was wrongfully granted 1,200 hours of paid leave worth more than $33,000. According to the state auditor, the hospital then reassigned the cars back to the security team and voided the incorrect accounting transaction.

Since 2019, the CDPH has issued three other citations to Coalinga related to lapses in its medical care,including two for lax adherence to COVID protocols, and another related to improper handling of a patient’s medical record after he was treated at an outside hospital. The DSH responded to the state by saying they were all isolated incidents, but subsequently updated their procedures for infection control and personal protective equipment.

In response to KVPR’s questions about why the facility’s high mortality rate in 2020, DSH pointed to age, higher-than-average COVID infection rates in surrounding communities, and high rates of psychiatric and chronic diseases among patients that are risk factors for both death and COVID.

“At Coalinga State Hospital, 67.9 percent of the patients had at least one COVID-19 medical risk factor (age over 60 years, Blood, BMI>30, Bowel/GI, Cancer, Circulatory, Diabetes, Immune, Renal, Respiratory). This percentage was the highest among DSH hospitals,” the statement read. “In addition to individuals with serious mental illness having a significantly higher risk of morbidity and mortality in general, there is emerging evidence that patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders are at a higher risk for COVID-19 mortality independent of other variables.”

All this is why Hydrick, who runs a blog about his experience at Coalinga, argues the hospital shouldn’t skimp on preventive care. “These examinations are vital for our population,” he said. “I’ve watched a lot of my friends die here at this hospital.”

A Coalinga State Hospital employee wasn’t surprised to hear of the facility’s high fatality rate. “The main reason that comes to mind is the age of our population,” said the employee, a mental health professional with more than ten years of direct patient access who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation from hospital administrators. But the employee has also heard patients’ concerns of slow or insufficient responses to medical issues. “Yes, I think there’s inadequate care,” the employee said.

Although the employee agrees that some other employees do appear to undervalue the patients’ lives, the bigger problems are systemic, stemming from hospital mismanagement and staffing issues. “When you’re short-staffed and they don’t have enough people to do that, or the people that you do have staffed have to do that instead of their regular jobs, then treatment takes a back seat. It’s more like dealing with emergency issues,” the employee said.

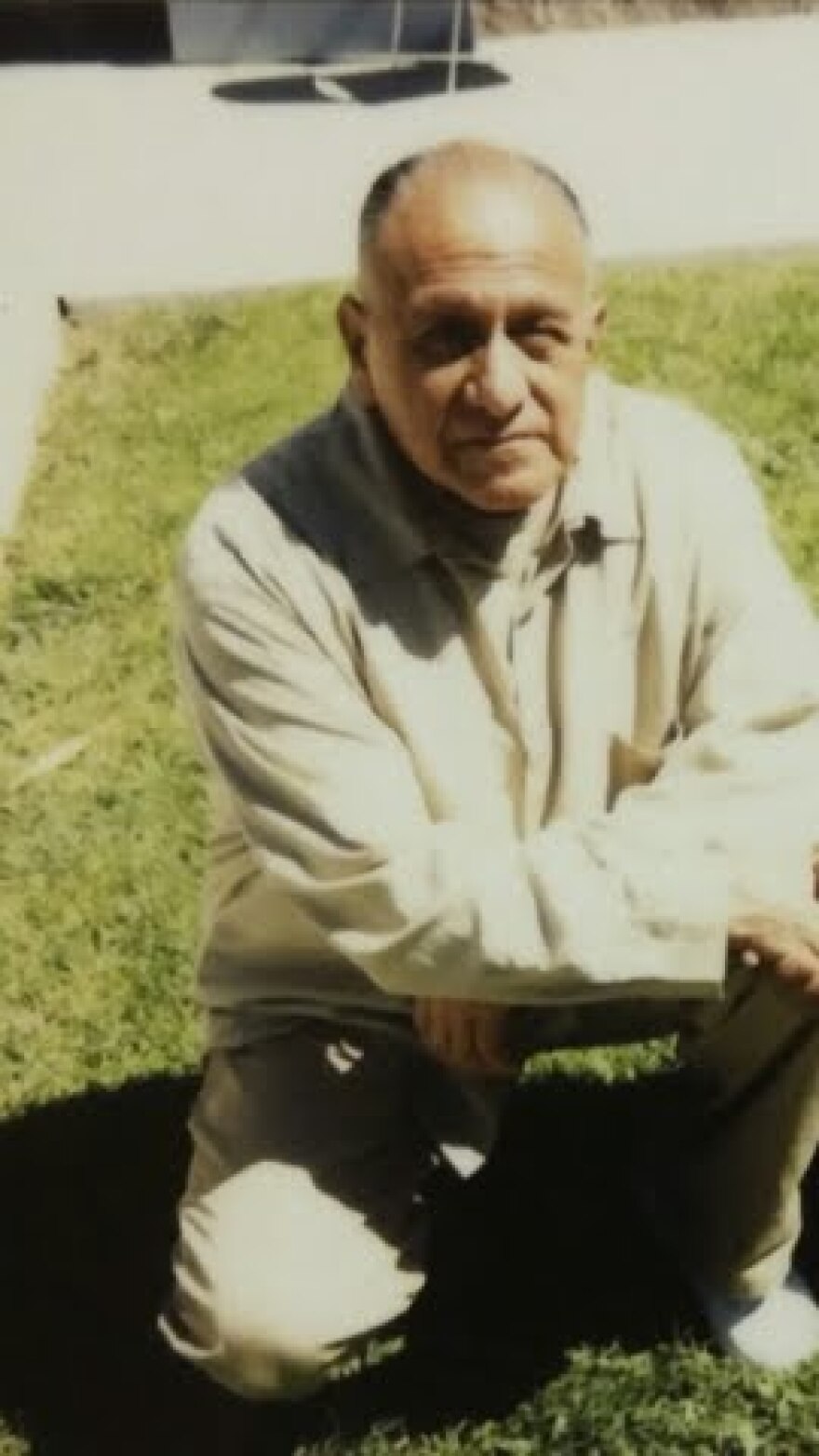

Meanwhile, some patients’ family members, like Annette Vallejo, say they simply don’t have enough information to know the quality of medical care their loved ones received. Vallejo’s father, Jose DeLeon, was one of those Coalinga patients who died last year. “I miss him calling me, I miss his voice, it hurts,” she said.

In January 2020, DeLeon was transported from Coalinga to Community Regional Medical Center in Fresno, where he was diagnosed with pneumonia and sepsis, then he died following cardiac arrest. But just days earlier, according to Vallejo, DeLeon had been feeling good. In their final phone call, he mentioned that he was heading to the medical unit for chest x-rays. “’Mija, I’m fine, I love you, and I’ll talk to you in a little while,’” she said he told her. “And I said ‘ok dad, I love you too.’”

According to his death certificate, DeLeon’s official cause of death was atherosclerotic heart disease. Eventually, Vallejo and her four siblings pieced together his final days after obtaining the medical records from his hospital stay in Fresno. But Coalinga never revealed the sequence of events that led him to be hospitalized in the first place, and so his care at the psychiatric facility remains shrouded in mystery. “We’re his daughters, you know, we have the right to know,” she said.

In another case, the hospital never informed a patient’s mother that her son had died. She found out only three weeks later,when she called to see if he’d gotten her Christmas card. “DSH makes every attempt to contact the next of kin or emergency contact,” the agency said in a statement earlier this year. “If the information DSH was provided is either inaccurate or outdated, this may contribute to the delay or inability to contact the next of kin or emergency contact.”

These families want accountability for their loved one’s deaths. Jeff Gambord, who also maintains a blog about his experience in the facility, wants legislators to push for an outside investigation. “That’s why a state audit is important, to find out what’s going on here,” he said. “Why haven’t the doctors been providing appropriate care, why has this happened, and what’s going to prevent it from going on in the future?”

The hospital employee agreed, adding that the outside monitoring agency should be federal, in order to look into how Medicare funds are being spent.

After all, according to hospital directives, all patients do have the right to “adequate, appropriate, and timely” health care, regardless of their criminal convictions.

You can read more about how this story was reported here.

This story was edited on July 7 to clarify the extent to which Terry Shenkman took on Coalinga patients as clients. In addition, a client of hers had been mistreated, not misdiagnosed, due to a lack of treatment in his native language.