This story received a 2022 National Edward R. Murrow Award from the Radio Television Digital News Association (RTDNA). It also received a 2022 Regional Edward R. Murrow Award from the Radio Television Digital News Association (RTDNA). Read more about the national Murrow award here and read about other regional Murrow winners here.

After over a year online, Madera South High School adopted a hybrid schedule in April so students could return to classrooms a couple of days a week.

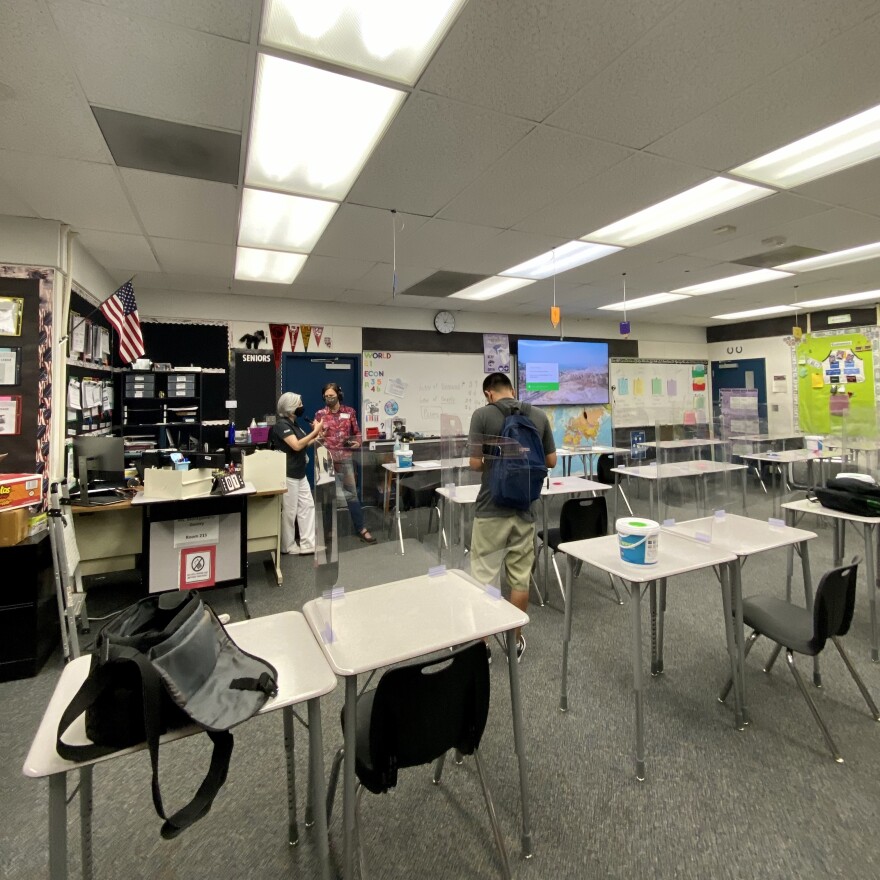

But inside Rodia Montgomery-Gentry’s 12th grade economics class in early June, it felt like school was already out. Desks with plastic dividers lined the room but there were only three students.

“Everyone, would you mind turning on your camera? It’s our last day might as well,” Montgomery-Gentry is heard addressing students on her screen.

Most of the students Montgomery-Gentry was talking to were still online. Out of 27 logged in, eight had their cameras turned on, but most of those cameras were pointed at the ceiling.

“The students have heard, probably every single class time, me announce, you know, ‘So and so are you here? Put in the chat if you're here. And mic yourself if you're here.’ Nothing,” said Montgomery-Gentry.

It was a challenging year for Montgomery-Gentry and other teachers. Just because students were officially in attendance, or at least logged in, that didn’t mean they were participating or even there.

Daniel Lupian Ceja, was one of the few students in the room. He says he had always cared deeply about school, but in the pandemic he lost his motivation, his drive. Online learning made classwork seem, well, empty.

“It felt like if it wasn’t in person, then it just didn’t feel as real. It felt like a phone call versus being there and talking to someone,” said the 18-year-old senior.

Madera Unified is a poor district. Nearly 90% of students receive a free or reduced price lunch.

Here at Madera South High, the vast majority of students are English learners. Seventy percent speak Spanish at home and others speak indigenous languages like Zapoteco and Mixteco.

So how are those students doing? KVPR filed a public records act request for the school’s attendance records. Officially, the chronic absenteeism rate was just 5%, meaning nearly all of its students were going to class.

But that’s not what teachers and students were seeing and even the district admits that official statistic is misleading.

“It’s inflated. I mean, it’s absolutely inflated,” said Alyson Crafton, Director of Student Services at Madera Unified.

She was in charge of making sure records were compliant with state requirements. But it was difficult to monitor attendance and engagement without the requirement for distance-learners to turn their camera on.

“You can literally be on your phone, on YouTube or with your friends -- and or sleeping,” said Crafton.

But that’s not how the district was supposed to count attendance.

Under a law signed by Governor Newsom last June, administrators were required to track not only whether students showed up, but how much they participated in distance learning -- for example, whether they communicated with their teacher or turned in assignments.

But even though we requested it, the district didn’t share that detail with us. And neither did other districts in the Valley, like Fresno and Clovis Unified. And, so Crafton said the true level of student engagement remains unknown.

“And quite frankly and I don’t know there’s any way to tell,” said Crafton.

However, Babatunde Ilori, executive director of accountability and communications at Madera Unified said the district does know the true level of engagement by utilizing several metrics including grades. According to Ilori, 18% of students received D's and F's before the pandemic. After the last school year, that number was 32%.

Senior Daniel Lupian Ceja was counted as present when he was online. He would log on, but he wouldn’t do the work. Eventually, taking a job pulling weeds from grape crops seemed like a more sane use of his time.

“I was mostly in the fields like working, trying to make money because that seemed more important to me at the time than just keeping up grades,” he said.

But when school reopened, he changed course.

“What helped me get back into school was realizing that if I don’t put in the effort, I might not graduate,” said Ceja.

In Montgomery-Gentry’s economic class, 11 students got D's and F's. That’s twice as much as during a normal year where she says the average is 4-5. Economics or civics is a graduation requirement, so students who fail this class can’t graduate.

Many students could get by with marked attendance by either logging in, turning in work, or having contact with teachers. But without the requirement to turn cameras on, and with piling work loads, Crafton said the number of D’s and F’s shot up the first semester.

“If they weren’t self motivated to learn, and even if they were. Some of the depression, some of the sadness, some of feeling overwhelmed, feeling very apathetic kicked in to a degree that really interfered with them,” she said.

Districts were required to reach out to students if they dropped off. Crafton says part of the district’s plan was more home visits.

This past year, the district logged more than 4,000 home visits. In a normal year, that number was 500. Visits ranged from engagement attempts to meal deliveries and award recognitions.

Despite the challenges, Crafton says she believes the law forced the district to make necessary changes to address individual student needs.

“What we sometimes lost sight of is the human compassion. And an understanding of why perhaps that family or that child that day or that month or whatever is not in place to receive any of the things that we want to teach him or her,” Crafton said.

The law allowing distance learning expires at the end of the month and students will return to classes five days a week in the fall.

Back in Ms. Rodia Montgomery-Gentry’s nearly empty classroom, she’s getting ready to sign off for the last day of school, addressing both students in the class and online.

“It's been an honor to be called your teacher,” she said, as she addressed the lone student in the room. “And it's been an honor to be called you guys' teacher.”

Tears begin to form in her eyes as she addresses a screen of digital squares.

“This is hard on you. It's hard on teachers, but you made it. You made it,” she said.

Gentry said she believes the most important lesson for students this year was resiliency, a life lesson they’ll carry into adulthood.

This report was produced by KVPR in collaboration with NPR's California Newsroom.