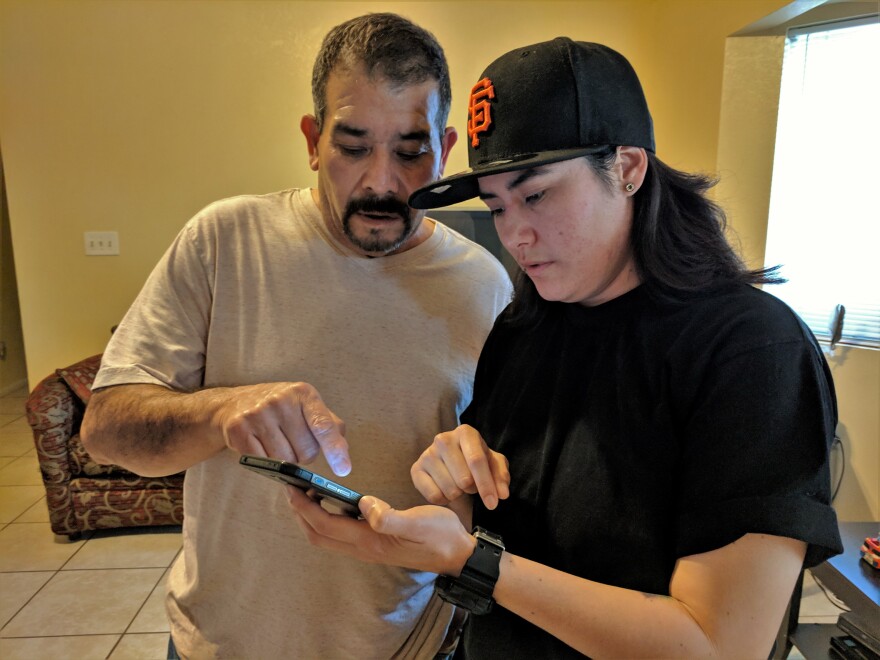

About five years ago, Jesus Gomez spent a month in the hospital. As he pulls out his phone to show me photos, he stops and smiles. “They’ll scare you,” he jokes.

Gomez scrolls through pictures of his head and torso covered in red splotches and thick brown scabs. “If they hadn’t treated me, I would’ve died,” he says in Spanish. “I would’ve been dead five years.”

His symptoms began small in 2013. “It started with an itch, and when I would scratch, it would break the skin and it would start to peel,” he says. Then came blisters.

He tried to wait it out. The Mexican restaurant where he worked six days a week didn’t provide insurance, and didn’t allow him sick time. But he knew he needed to see a doctor when blisters had broken out on his chest and back. He paid out of pocket to see a general practitioner. “They did a biopsy and told me it was an allergy,” he says.

But the allergy medication he was prescribed didn’t work. Neither did another doctor’s treatment for psoriasis. The disease progressed, blisters and open sores covering more and more of his body. Without insurance, other doctors turned him away, and emergency rooms failed to connect him with a specialist. For almost a year, he was ping-ponged around a disjointed system that didn’t know how to treat him and didn’t have the continuity to follow through. “It affected me emotionally because no medicine was helping,” he says. “I thought, was there no cure for what I had?”

“It was horrible because no one could give him answers, and just seeing that he was getting worse and worse instead of better, it was hard,” says his 27-year-old daughter Jessica Gomez.

By early 2014, her father’s body was oozing and bloody. He had to quit his job. He lost his hair. Once, Jessica remembers, she had to cut his shirt off—and a lot of his skin came off with it. “Because he had a lot of pus that would come out, he smelt literally like his body was rotting,” she says. “Like he was dead.”

One night in February 2014, his ex-wife called a family friend who was a nurse. When she saw that he was shaking, feverish, his limbs swollen and retaining water, she told them he needed to get to a hospital. She rushed him to the emergency department at Kaweah Delta Medical Center and later told them, if he hadn’t gotten care that night, he likely would’ve died.

The last thing Gomez remembers is signing paperwork, probably for the emergency Medi-Cal coverage he should have been given earlier. He awoke the next day at Community Regional Medical Center, where he had been transported to the intensive care unit for burn victims.

“I walked into the burn unit and I saw a man who had probably 5 percent of the skin on his body intact,” says Dr. Greg Simpson, a dermatologist at Community Regional and UCSF Fresno, which run the only burn center between Bakersfield and Sacramento. “He was basically looking like someone that was on his death bed.”

Almost immediately, Simpson recognized the signs of pemphigus vulgaris, an autoimmune disease in which the immune system attacks its own skin cells. “The way we think about a lot of these autoimmune diseases is they’re like a light switch,” he says. “Something happened to turn the light switch on, and light switch is on until we do something to turn it back off.”

The only treatment that turns that light switch off is chemotherapy indicated for treating cancers like leukemia and lymphoma. It’s no wonder allergy drugs didn’t work.

The disease is rare, just a few cases in every half a million people. But Simpson says he tends to remember those patients distinctly because their symptoms are so severe. “They’re taking a lot longer to get picked up by the system and treated, and they’re just seen way farther along than they should be,” he says.

Simpson says most dermatologists could diagnose pemphigus vulgaris relatively easily. But like Gomez, many patients never find their way to them. The California Healthcare Foundation estimates less than two-thirds of specialists accept Medi-Cal patients or the uninsured—which together are estimated to make up more than half of the San Joaquin Valley. Plus, the Valley is chronically underserved by all doctors, particularly specialists.

Jesus Gomez was released from the burn center after a month, his wounds so extensive he needed to be sedated each time his bandages were changed. Today, he keeps the disease at bay with infusions once or twice a year of a new chemotherapy drug called Rituximab. He calls Dr. Simpson a gift from God.

Now 55, Gomez now lives with his kids and two nephews. It seems to suit his daughter Jessica. “When I was little, my mom fell into depression after she had me,” she says, her voice cracking. “My dad had to step in and help me because my mom wasn't able to. So I feel like it got reversed and I got to pay him back.”

Gomez is out of work on disability leave and his skin still breaks out in harsh sunlight and heat. But every morning he can, he tends to his garden, growing herbs like cilantro and mint. There’s the branch he stuck in the ground that grew into a mulberry tree, and the rosebush he shaped into a heart.