This story received a 2021 Golden Mike Award from the Radio Television News Association of Southern California. Read about other winners here.

A https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=npc3pYH7zcU">documentary produced in Burma in the late 1990s shows two young Hmong women in traditional dress dancing. They’re encircled by other villagers and everyone is singing a goodbye song to filmmaker Su Thao.

“He went to Burma to find, kind of like the lost Hmong people there. He did a documentary. The whole town came out to welcome him. He had a conversation with the village elders,” says Steve Thao, Su Thao's oldest son. Su died of COVID-19 last month and his funeral is this weekend in Fresno.

The documentary was a big deal, Steve says, because it gave other Hmong communities all over the world a chance to compare culture, history and life experiences. But it was also a dangerous trip to make because of Burma’s ongoing civil war.

By the time Su Thao made this documentary, he’d already been a well known film distributor of VHS videos dubbed in Hmong. They were mostly romantic and action films from Thailand as well as films from Bollywood. His company was called ST Universal Video.

“A lot of homes in America would have these videos,” Steve says. “We would send thousands of videos across the country and sell them through different Hmong grocery stores.” They also distributed them internationally.

Steve says his dad even made documentariesof his native Laos in the early nineties, years after he and tens of thousands of other Hmong came to the United States as refugees.

“The government was still closed off to most people,” he says. “So it was really an amazing thing for people here to see Hmong people in Laos, to see the land of their forefathers and see some of their relatives on video.”

His image and voice on the documentaries made him a kind of celebrity. “It really put him on the map,” Steve says. “People were starving for that kind of information and starving for that kind of content.”

Like many older Hmong refugees in Fresno, Su Thao fought in the CIA’s secret war in Laos. He was a second lieutenant and helped direct bombers and fighter pilots on air missions. When the Pathet Lao won the civil war in Laos in 1975, Su and his family tried to get on one of the planes that General Vang Pao had brought in for officers like him. Steve was only 5 years old.

“I think it was the last C-130 and I remember him throwing me onto the plane and I just remember the image of people all over,” he says. “There’s an iconic picture of a C-130 with thousands of people around it.”

Su and Steve Thao both got on the plane headed to Thailand. But somehow in the crush of desperate people pushing to get on board, Su’s pregnant wife and daughter got separated from him and didn’t make it on the plane.Many of Su’s other family members were also stuck in Laos. His niece Tru Chang says her family was terrified Vietnamese soldiers would kill them.

“One night they heard footsteps outside the door and they thought ‘Oh my gosh, we are gonna be caught now’ and they all were frightened, they started crying and the footsteps got closer to the door,” Chang says.

There was a knock on the door. Their hearts stopped. They thought this is it. But then they heard a familiar voice. It was Su Thao. He had risked his own life to come back to Laos to rescue the rest of his family including his wife and daughter.

“They opened the door and Uncle Su said to them, ‘don’t worry I’m going to take you guys,’” Chang says.

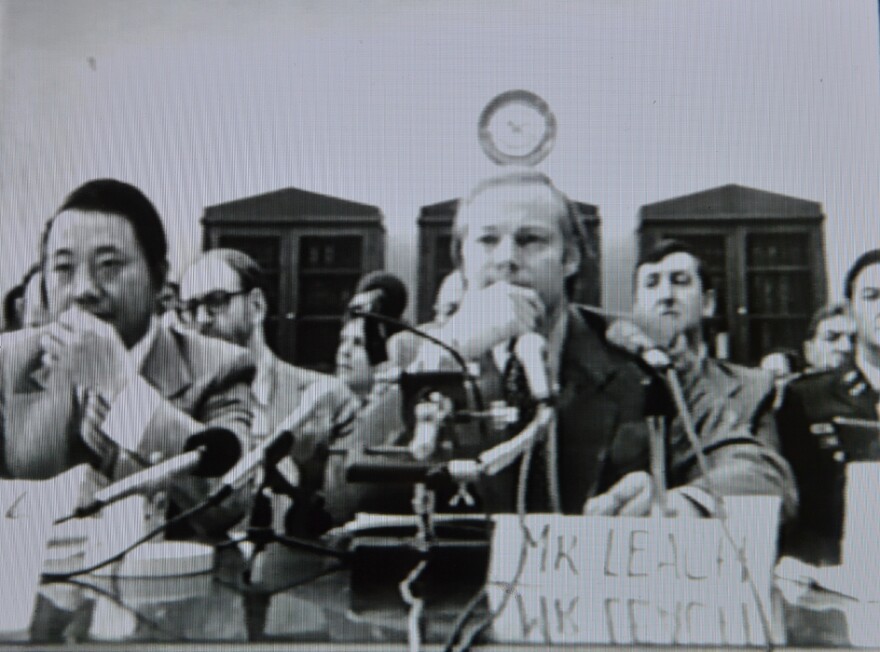

He hired a bus and bribed some patrol guards to let them through. Su talks about the journey in a documentary about Hmong refugee resettlement by Michael Korpi called City of Refuge.

“May 14, 1975. On that day we lost our country to the communists,” he says in the film. “And we decide to flee to Thailand. FInally we crossed the Mekong River safely into Thailand. We stay in the refugee camp 10 months and then we came to America.”

Su’s family was sponsored by the Third Reformed Church in Pella, Iowa, a Dutch immigrant town known as the City of Refuge. HIs family was the first to arrive in Iowa but many others followed.

After a couple of years, Su got a job working for the Iowa Refugee Services in Des Moines. He helped new Hmong families acclimate and find jobs. He worked long hours translating.

In the documentary, he talks about receiving phone calls 24 hours a day. “Doctors need interpretation or refugees, they need help, they call me at home,” he says.

But Su and his family missed the town of Pella and they often drove back on the weekends to attend the Hmong Christian Church. Su had been raised Christian in Laos.

In the early 1990s, Su moved to Fresno. He wanted to be around a large Hmong community where he could find actors to dub film parts. He also got involved with Hmong radio and was a host on KBIF 900AM and an owner of KQEQ 1210AM.

Just this year he had agreed to move to Minnesota where several of his nine children live. But in June, he had a stroke. He needed physical therapy so he went to a rehab facility at a nursing home. His daughter Vanh Thao says the plan was to keep him there for four to six weeks and then bring him home. But instead, he got a fever and started shaking.

“They sent him to Clovis Community Hospital. And as soon as he got there they tested him right away. He was positive for coronavirus,” Vanh says.

He’d been in high spirits, Vanh says, but the virus made him so ill. She and her siblings saw him multiple times over a Zoom connection on the internet. The first day he gave them the thumbs up. By his last day, July 30th, he was wearing an oxygen mask.

“And then we didn’t think he could hear us but he did because the way he was sitting was kind of like on the side and the nurse was wiping tears with a tissue,” she says.

It was surreal, Vanh says, even eerie to watch her 72-year-old father die, not in person but over a screen.

“It was a real struggle to watch him breathe and not being able to...it was like watching him suffocate,” she says.

The disease is horrible, Vanh says. But what she really hates is that people are dismissive when someone who is older dies from it.

“Because the old people, it’s somebody’s mom or dad or brother or uncle,” she says.

Somebody’s brother, uncle, father. Su Thao was all of those but he was also someone who did so much for the Hmong community. And if he hadn’t caught the virus, she wonders, what other amazing things would he have done?