On a bright afternoon in June, a group of protesters wearing masks gathered in a dusty parking lot outside a prison in rural Kings County. One of them held a megaphone up to a cell phone. “My name is Jacob Benitez, I’m an inmate calling from Facility F right here at Avenal State Prison,” crackled the voice on the other end of the call.

Benitez had called in to the protest to demand officials do more to contain a COVID-19 outbreak that had just begun at Avenal, calling attention to the difficulties of social distancing and other protective measures that proved challenging in the confines of prison. “I’ve found that a great deal of negligence toward the inmate population as well as lower level staff has taken place,” he said.

Although that is disputed by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), the agency that oversees the state’s prisons, what’s more clear is that the pandemic has disrupted normalcy.

Benitez has been in prison since 2009, and the pandemic has put off many programs that he says have made prison life more tolerable. He’s a peer mentor, has enrolled in self-help classes, and he’s studying for an associate’s degree in business management.

Thanks to the pandemic, however, college classes have been postponed indefinitely, and those self-help programs are “pretty much gone,” Benitez says in an interview. A CDCR representative confirms that many rehabilitative and educational programs have been postponed until they can be done safely.

Benitez is also an elected member of an inmate advisory council, which serves as a liaison between administrators and the incarcerated population. Since March, however, he says meetings have been sporadic, and it’s been tough to keep on top of the prison’s shifting approach to containing the pandemic. “This is a big entity that we’re facing,” he says. “Can we at least get some transparency?”

After a tremendous spike in early June and many fluctuations since,Avenal’s cumulative tally of nearly 3,000 COVID-19 cases is now the highest of any of California’s state prisons. Data from the New York Times suggestit may now be the highest of any correctional institution in the country. And yet so many men there can’t say with any uncertainty how many of their fellow inmates have contracted the virus or died of it, and they feel that the system is keeping them in the dark as it constantly changes policies on measures like mask wearing and shared yard time. As officials work to contain the virus, inmates claim life is chaotic and confusing, and they worry that the pandemic is taking a psychological toll.

“This prison has changed their mind dozens of times, and the inmates are victims of it,” says John Walker, who’s been incarcerated at Avenal for the last year. “They can’t get settled, they can’t relax, the mental health department is filled with cases of people with anxiety and depression over all this crap.”

Walker is one of the thousands of inmates at Avenal to contract the disease since the first case was reported at the prison in May. Watching the virus spread outside the prison, Walker says he was at first dubious of the pandemic, skeptical of its severity, then fearful as it spread its way from yard to yard. He says his symptoms were mild, but seven men incarcerated at Avenal have died. “I don’t think any of us knew how serious the situation was going to be,” he says.

Ed Welker, who’s been at Avenal for only a few months, had a tougher bout with the virus, saying he suffered debilitating fatigue and a migraine that persisted for days. What made it worse, he says, was being relocated to different dorms, twice, while recovering. A representative of CDCR confirmed that different buildings have been set aside for those in various stages of quarantine, but Welker and many other inmates say they’re given little notice or explanation for why they’re being moved. “Everything is kept secret, they’ll come to you and they’ll say ‘hey, pack your stuff, you’re moving,’” he says. And when he asked why, he says he was told, “because Sacramento says you’re moving.”

On top of all this, visitations have been postponed indefinitely. Although the prison has discounted JPay, a messaging service used by incarcerated people and their loved ones, and designated a few free call days each month, the men at Avenal have had no face-to-face contact with family or friends for months.

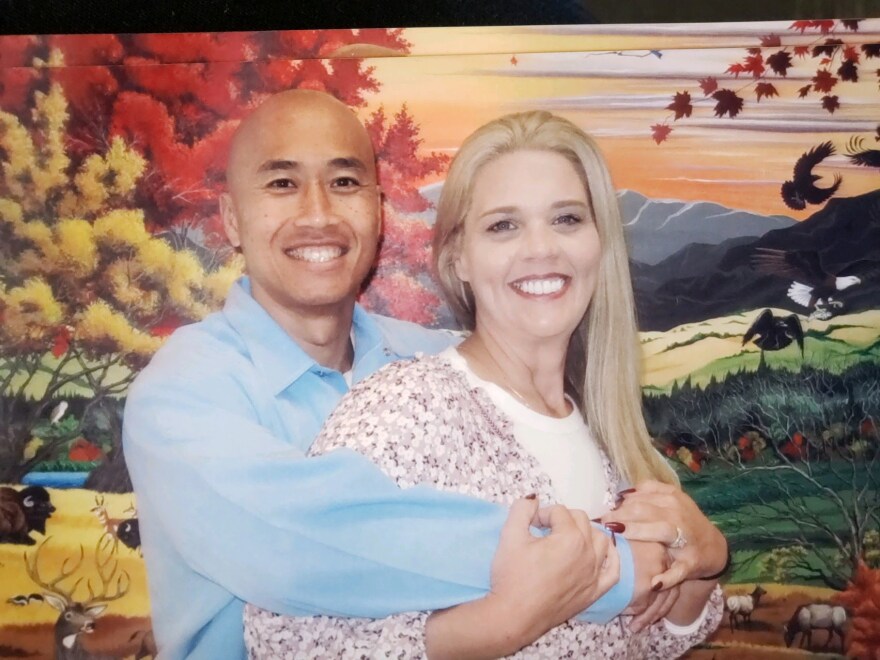

Those loved ones are essential, many say, and not just for morale. They also serve as news sources. “Wives on all six yards all communicate well with one another,” says Michelle Tran, whose husband has been at Avenal for nearly four years. She’s also an organizer with the advocacy group Families United to End Life Without Parole (FUEL), which led the protest outside the prison in June.

Tran says the men inside Avenal receive only bits and pieces of information from administrators, which her network of spouses tries to synthesize into something more comprehensive. “If something’s going on somebody will ask a question or send out something on Facebook to where we all can interact with one another,” she says. An Inmate Family Council also meets with prison representatives once a week.

“Traditionally, and in general, correctional administrators don’t do the best job of communicating with the people who are incarcerated there,” says Don Specter, an attorney and executive director of the Prison Law Office, where he’s currently involved in a number of lawsuits advocating for better medical and mental health care for those incarcerated in California’s state prisons.

Specter says a prison constantly changing policies for its population isn’t criminal, but it can be harmful when added to confinement and a lack of control. “That creates an incredible amount of anxiety, understandably,” he says.

The anxiety inmates are feeling can have very real consequences, says UC Merced psychologist Jennifer Howell. “When people are worried and they feel like they have no control, and uncertainty is at its maximum point, that is when you’re seeing lots of negative psychological and physical health outcomes,” she says.

Howell has studied the effects of the pandemic on people across the U.S. and China. She says she’s observed high amounts of chronic stress and disrupted sleep, which not only affect eating and exercise, but can also impair immune function, cognition, and long-term health. And that’s just for people outside of prison.

“That kind of environment, where you have a very fixed schedule, where you’re not necessarily in control over how much space you have from other people, when you’re not necessarily in control of government policies that you are sort of being told what to do, I imagine it’s just exacerbating these effects incredibly,” she says.

In an email statement, a CDCR representative writes that up-to-date information on the pandemic airs on television channels throughout the state prison system and is also provided on written materials. “Posters and handouts have also been distributed and put up for display on topics such as social distancing, proper handwashing and COVID-19 warning signs,” the statement reads. “Updated handouts and posters are provided as information on COVID-19 changes.”

The agency also says that all inmates get mental health check-ins during daily COVID-19 screenings with nurses. The prison has paused some group treatment programs but moved others onto prison television. “The well-being and safety of the incarcerated population and staff within CDCR…is our top priority,” the statement reads. “We understand how vitally important it is to deliver comprehensive mental health services within our institutions at all times, but especially during these extraordinary times of heightened uncertainty.”

Still, Ed Welker worries his fellow inmates won’t get the services they need if they don’t take the initiative to ask for them. He knows the benefits of seeking help: Almost 30 years into a sentence of life without parole, he started therapy years ago after a suicide attempt. “It’s given me the ability to talk to somebody and get a different perspective,” he says. “It’s given me coping tools, it’s given me a sense of purpose.”